Often on a whale watch trip, I ask our guests if they have been whale watching before, and if so, what was their favorite experience. By far, they tell me about the time they saw a mom with her baby. Whether it was because the calf was curious about the boat, playing around at the surface or even simply nursing or sleeping, people seem to connect with the mom/baby experience.

Humpback whale calves are born in the winter at lower latitudes where the water is warm. They then follow their mother to the colder, productive water of higher latitude areas so that mom can feed. (Warm water is much less productive than cold water so mom doesn’t eat anything between the time she leaves cold water and then returns about 5 months later.) The calves typically spend less than a year with their mothers before they are on their own, so when we see them, they are already a few months old.

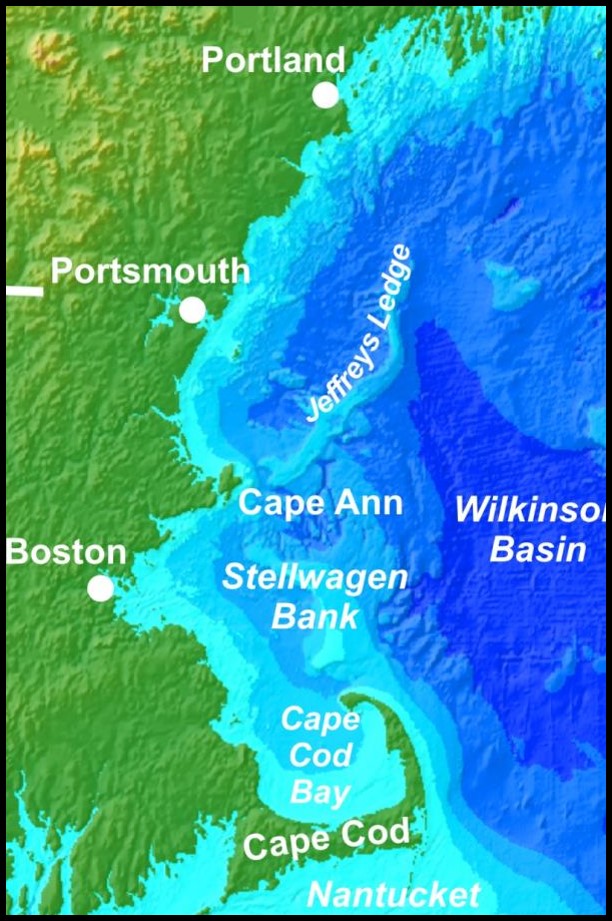

Researchers have well-documented humpback whales in the Gulf of Maine since the 1970’s and can identify individual whales based on natural markings that do not change much over time. Stellwagen Bank has been very well studied. Jeffreys Ledge (our primary study site) has been less intensely studied, although Blue Ocean Society has over 20 years of data from here. It has been common knowledge that a humpback calf tends to return to the same feeding areas that its mother took it to during its first year before weaning. Several scientific papers support this theory. However….

The vast majority of those cute, playful, curious calves that our guests love to see are not being re-sighted in our area, Jeffreys Ledge. One of our 2016 interns, Erin Hord, took a look into our data and found that only 16% of the calves that we saw between 1998 and 2015 were seen again on Jeffreys Ledge after they had weaned. Of those 11 individuals, only 2 have been seen in two or more years on Jeffreys Ledge.

So what does this mean? Well, based on our collaborations with other organizations including Allied Whale and Center for Coastal Studies, we know that some of the calves we saw during those years have been seen in other areas of the Gulf of Maine as yearlings or adults. But what about the rest of them? More work certainly needs to be done to determine if the survival rate of calves is actually decreasing. The North Atlantic humpback whale population was recently removed from the Endangered Species List since scientists believed that this group was no longer in danger of becoming extinct (in other words, the population is increasing). We plan to continue this small-scale study and collaboration and hope to see all those cute little baby whales grow up safely and come back to visit us!