During the spring, summer, and fall months we often hear about red tide (harmful algal blooms), and many people ask us about it at the Blue Ocean Discovery Center. This month we will explain what it is, what causes it and why you should be aware of it.

Many of us are knowledgeable about the microscopic organisms we collectively call “plankton” that live in the ocean. The term plankton comes from the Greek “plankter” and means any organism that drifts or can’t swim against the currents. Planktonic organisms can be small animals like copepods and krill and we call these zooplankton. Microscopic plant-like organisms are responsible for the water’s green color and these are called phytoplankton. Caribbean water doesn’t have a lot of phytoplankton and is usually crystal clear blue rather than the green we are used to here in the North Atlantic.

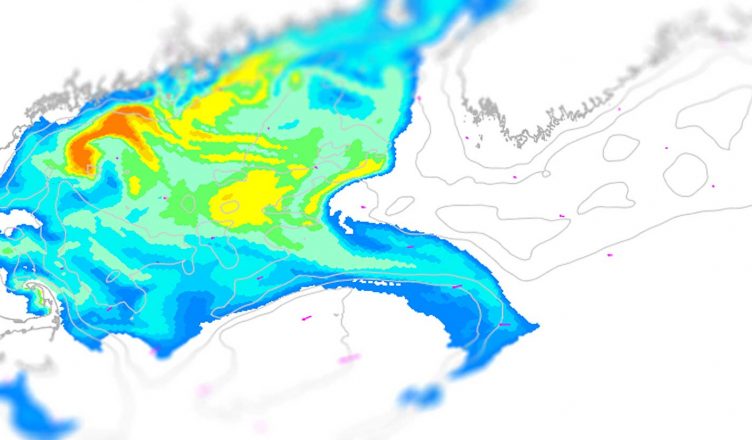

Phytoplankton is the base of the food chain in the ocean, much the same way that plants are the base of the food chain on land. Just like plants on land depend on nutrients or fertilizers, plant-like phytoplankton in the ocean depend on nutrients as well. Nutrients in the ocean settle on the ocean floor and are stirred up by many natural events including storms. We say that the nutrients “upwell” to the surface and these upwellings trigger phytoplankton growth or blooms. These events also depend on the sun’s strength, the water temperature, and the wind direction and they usually occur in the spring and in the fall. Think of all the Nor’easters and hurricanes we get in the spring and fall.

Some phytoplankton, especially those that live in more southern areas, have photosynthetic pigments that turn the water either brown or red. When these phytoplankton bloom, people see the water color change and know that there is a “red tide”, although the phenomenon has nothing to do with the tide. In New England, we don’t see a color change in the water, although we still call it a red tide when the phytoplankton blooms.

The reason that we are concerned about a red tide occurrence is that some phytoplankton contain neurotoxins. These toxins bioaccumulate in animals that eat the phytoplankton and can cause Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP). As the name implies, the toxin causes paralysis in animals that consume the phytoplankton. Any animal that eats a lot of the poisonous phytoplankton may become paralyzed. As small animals low on the food chain ingest the toxin-bearing phytoplankton, they concentrate the poison in their bodies. Larger animals that eat them get larger doses of the neurotoxin with each meal. As a result, mollusks, fish, birds, marine mammals, and humans can all be affected by the tiny phytoplankton’s poison. This is why large numbers of dead fish wash up on the beaches in Florida.

Red Tide or a harmful algal bloom (HAB) can be life-threatening to humans. Within two hours of eating seafood that contains the neurotoxin, humans may experience tingling, burning or numbness in the extremities. Drowsiness and incoherent speech may follow with eventual paralysis of the diaphragm and death. PSP is, of course, preventable: you just need to know that the seafood you eat is safe.

The government has several monitoring programs that assess the toxins in filter-feeding mollusks. In our area, the monitoring program consists of weekly collection and testing of blue mussels from the Hampton/Seabrook Harbor from April to the end of October. The offshore waters at the Isles of Shoals are also tested. When the PSP toxin levels in the blue mussels reach 80 micrograms of poison per 100 grams of mussel tissue, the harvest areas are closed. The harvest areas are all posted with warning signs and the state has a hotline detailing closures. The problems arise when people harvest their own mollusks and are unaware of the potential dangers.

Seafood that you buy in markets or restaurants should be safe, thanks to government testing. We often think about all the people who were affected by HAB’s and PSP before the testing was done. The seacoast of New Hampshire was inhabited by Native Americans for thousands of years. How many of them died from the effects of the tiny phytoplankton?

Image: A physical-biological model of wind stress and simulated surface cell concentration of the harmful algal bloom Alexandrium catenella in the Gulf of Maine from June 19, 2019 / NOAA Image